KANSAS CITY, Mo. — Sister Thea Bowman, a trailblazing African-American sister who was the first and only black nun in her religious congregation and the first black woman to address the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, continues to inspire members of her order and others she touched throughout her life.

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — Sister Thea Bowman, a trailblazing African-American sister who was the first and only black nun in her religious congregation and the first black woman to address the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, continues to inspire members of her order and others she touched throughout her life.

The Mississippi native was a Franciscan Sister of Perpetual Adoration. Her position in religious life allowed her to address racism in the Catholic Church at a time when the culture and traditions of African-American Catholics still were not widely accepted.

“Sister Thea always encouraged people to stand up for their rights and she continues to inspire,” Sister Eileen McKenzie, congregation president wrote in an emailed statement to the Global Sisters Report.

“As FSPA and the Leadership Conference of Women Religious pledge to unveil white privilege and purge the destructive effects of racism, we recognize Sister Thea’s cause to sainthood serves as a sign of the times. We believe she’d find hope that in this canonization process, there’s continued movement toward racial equity.”

The USCCB voted at its fall general assembly last November in Baltimore to advance Sister Bowman’s cause, opening the way for a diocesan commission to determine whether she lived a life of “extraordinary and heroic virtue.”

She was declared a “servant of God” in May 2018, when her home Diocese of Jackson, Miss., requested the bishops endorse opening her cause for sainthood. Jackson Bishop Joseph R. Kopacz read the edict opening the investigation and celebrated a special Mass Nov. 18, 2018.

Sister Bowman died of cancer March 30, 1990, at age 52.

Sister McKenzie said her congregation will follow the Jackson diocese’s lead as the process moves forward and that the community’s archives are open to commission officials.

There was a buzz in the motherhouse before and after the bishops’ vote, she said.

“We’re looking around with eyes wide, saying, where is this going?” Sister McKenzie told Global Sisters Report. “It’s a fascinating time, and we’re having lots of conversations about how providential this moment is.

She added that Sister Bowman in 1989 challenged the bishops on racism, and her message of reconciliation is still needed.

Born Bertha Bowman Dec. 29, 1937, in Yazoo City, Miss., she was the daughter of a doctor and a teacher. She attended Holy Child Jesus School in Canton, 38 miles from her birthplace, run by the religious congregation she eventually joined. At age 8, she decided she wanted to become a Catholic and knew as a young teenager that she was called to consecrated life.

In the 1950s, she studied at Viterbo College in La Crosse, Wis., where the order is based, while preparing to enter the convent. She later studied at The Catholic University of America in Washington.

‘We unite ourselves with Christ’s redemptive work when we reconcile, when we make peace, when we share the good news that God is in our lives, when we reflect to our brothers and sisters God’s healing, God’s forgiveness, God’s unconditional love.’

— Sister Thea Bowman

Renowned for her preaching, she took her message nationwide, speaking at 100 venues a year until spreading cancer slowed her. Music was especially important to her. She would gather or bring a choir with her and often burst into song during her presentations.

In addition to her writings, her music resulted in two recordings, “Sister Thea: Songs of My People” and “’Round the Glory Manger: Christmas Spirituals.”

Sister Marla Lang professed vows with the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration in the same class as Sister Bowman.

She said entering religious life is jarring for anyone, and Sister Bowman had the additional pressure of being in an all-white congregation in an all-white city, not to mention the cultural – and weather-related – shock of moving to Wisconsin from the Deep South. But if Sister Bowman was troubled by her circumstances, Sister Lang said, she didn’t show it.

“She had her spirituals, the music that was so beautiful. Most of us had been living with little or no contact with anyone of African descent, but her voice was so beautiful, it was just a very rich experience,” Sister Lang said.

Sister Mary Ann Gschwind was Sister Bowman’s roommate during the summer of 1966 at CUA. Sister Gschwind is the Franciscan sisters’ archivist and has been sworn in as a member of the historical commission for the sainthood cause.

Even at CUA, Sister Bowman was unique. Sister Gschwind said African-American sisters were on campus, but they belonged to African-American congregations. Because the sisters still wore traditional habits, it was easy to see that Sister Bowman was from a white congregation.

Even at CUA, Sister Bowman was unique. Sister Gschwind said African-American sisters were on campus, but they belonged to African-American congregations. Because the sisters still wore traditional habits, it was easy to see that Sister Bowman was from a white congregation.

“It took a lot of nerve for her to join our community,” Sister Gschwind said. “I don’t think I could have done it if the situation were reversed.”

The investigation into Bowman’s life will have no shortage of material to examine. The congregation’s archives contain three file drawers of Sister Bowman’s speeches – most of which she wrote on scrap paper to avoid waste – and 20 bankers boxes of documents.

Dan Johnson-Wilmot was Sister Bowman’s colleague at Viterbo in the 1970s, where he was a music department professor and she taught English and studied voice.

“Anyone who went to her presentations, I don’t think she ever had one where she didn’t sing,” Johnson-Wilmot said. “She had an uncanny gift. It didn’t matter who was there, she could weave a song into just about any kind of presentation she was giving, and people were just struck when she began singing because it was always from her heart and soul.”

Johnson-Wilmot said the two became fast friends after an incident that started out ugly but became just another sign of how Sister Bowman could unite people.

Several African-American students from Canton, Miss., at Viterbo formed the core of Hallelujah Singers, a gospel choir Sister Bowman established. The choral group Johnson-Wilmot directed was invited to sing at a local function, but learned an earlier invitation to the Hallelujah Singers had been withdrawn when organizers learned the singers were African-American.

Johnson-Wilmot said he called the organizers and said his group wouldn’t sing unless both groups were invited. In the end, he said, both groups sang and the event was a success.

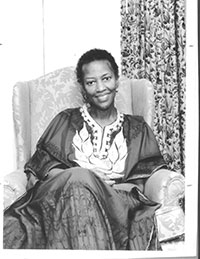

Sister Thea Bowman is pictured at a Walsh University event held on Sept. 18, 1989. All photos courtesy of Sister Thea Bowman Cause for Canonization websiteSister Charlene Smith of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration was Sister Bowman’s friend for 35 years and is treasurer of the Thea Bowman Black Catholic Education Foundation. She also co-wrote the book “Thea’s Song.”

Sister Thea Bowman is pictured at a Walsh University event held on Sept. 18, 1989. All photos courtesy of Sister Thea Bowman Cause for Canonization websiteSister Charlene Smith of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration was Sister Bowman’s friend for 35 years and is treasurer of the Thea Bowman Black Catholic Education Foundation. She also co-wrote the book “Thea’s Song.”

She said Sister Bowman’s parents worried about her joining an all-white religious order in the North.

“Her dad said, ‘They’re not going to like you up there.’ She said, ‘I’ll make them like me,’” Sister Smith recalled. “She spread joy even during her struggle with cancer. She was always spreading joy and happiness through her songs and her wisdom.”

In 1989, Sister Bowman returned to La Crosse for a symposium, but was so sick that Sister Smith was certain she would be unable to speak at the event. “They rolled her out in her wheelchair and she absolutely electrified the whole audience there,” Sister Smith said.

When Sister Bowman spoke to the U.S. bishops in June 1989, less than a year before her death from bone cancer, she was blunt. She told the bishops that people had told her black expressions of music and worship were “un-Catholic.”

She began by singing “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” a rebuke to the shepherds of a Church that often neglects its members of color. “Can you hear me, Church?” she asked. “Will you help me? Jesus told me the Church is my home.”

Sister Bowman pointed out that the universal Church includes people of all races and cultures and she challenged the bishops to find ways to consult those of other cultures when making decisions. She told them they were obligated to better understand and integrate not just black Catholics, but people of all cultural backgrounds.

Catholic News Service reported that her remarks “brought tears to the eyes of many bishops and observers.” She also sang to them and, at the end, had them all link hands and join her in singing “We Shall Overcome.” They gave her a rousing ovation.

Sister Gschwind said her friend’s challenge of the bishops and having them embrace her in response is known to many in the community as “her first miracle.”

Sister Smith noted that Sister Bowman must be “getting a big kick” out of the canonization process.

“She said, ‘I just always try to let my little light shine,’” Smith said. “And she did.”

— Dan Stockman, Catholic News Service

‘I try each day to see God’s will’

Mary Woodward, diocesan chancellor in Jackson, Miss., displays the edict for the canonization cause of Sister Thea Bowman Nov. 18, 2018, at Cathedral of St. Peter the Apostle. Jackson Bishop Joseph R. Kopacz, at left, read the edict at the start of the Mass. (CNS | Maureen Smith, Mississippi Catholic)A self-proclaimed “’old folks’ child,” Thea Bowman was the only child born to middle-aged parents, Dr. Theon Bowman, a physician, and Mary Esther Bowman, a teacher. At birth she was given the name Bertha Elizabeth Bowman. She was born in 1937 and reared in Canton, Miss. As a child she converted to Catholicism through the inspiration of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration and the Missionary Servants of the Most Holy Trinity, who were her teachers and pastors at Holy Child Jesus Church and School in Canton. These religious communities nurtured her faith and greatly influenced her religious vocation.

Mary Woodward, diocesan chancellor in Jackson, Miss., displays the edict for the canonization cause of Sister Thea Bowman Nov. 18, 2018, at Cathedral of St. Peter the Apostle. Jackson Bishop Joseph R. Kopacz, at left, read the edict at the start of the Mass. (CNS | Maureen Smith, Mississippi Catholic)A self-proclaimed “’old folks’ child,” Thea Bowman was the only child born to middle-aged parents, Dr. Theon Bowman, a physician, and Mary Esther Bowman, a teacher. At birth she was given the name Bertha Elizabeth Bowman. She was born in 1937 and reared in Canton, Miss. As a child she converted to Catholicism through the inspiration of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration and the Missionary Servants of the Most Holy Trinity, who were her teachers and pastors at Holy Child Jesus Church and School in Canton. These religious communities nurtured her faith and greatly influenced her religious vocation.

Growing up, Thea listened and learned from the wisdom of the “old folks,” the elders of her community. Ever precocious, she asked questions and gained insights on how her elders lived, thrived and survived. She learned from family members and those in her community coping mechanisms and survival skills. These skills proved essential as she navigated through the horrid experiences of blatant racism, segregation, inequality and the struggle for Civil Rights in her native Mississippi. At an early age, Thea was exposed to the richness of her African-American culture and spirituality, most especially the history, stories, songs, prayers, customs and traditions. Moreover, she was cognizant that God loved and provided for the poor and the oppressed. Her community instructed her, “If you get, give – if you learn, teach.” These life lessons instilled in her an abiding love for God and to be charitable to toward those most in need.

For Thea Bowman, her conversion to Catholicism was rooted in what she witnessed: she was attracted to the Catholic Church by the example of how Catholics seemed to love and care for one another, most especially the poor and needy. For Thea, she was impressed by how Catholics put their faith into action. At the age of 15 she told her parents and friends she wanted to join the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration and left the familiar Mississippi terrain to venture to the unfamiliar town of LaCrosse, Wis., where she would become the only African-American member of her religious community.

At her religious profession, she was given the name “Sister Mary Thea” in honor of the Blessed Mother and her father Theon. Her name in religious life, Thea, literally means “God.” She was trained to become a teacher and taught at all grade levels, eventually earning her doctorate and becoming a college professor of English and linguistics.

The turbulent 1960s was a period of transformation for a nation torn by racial strife and division. The United States was confronted by the quest for justice and racial equality for all Americans. The late 1960s was also a time of transformation for Sister Thea Bowman: both a spiritual and cultural awakening. The liturgical renewal of the Second Vatican Council encouraged Sister Thea to rediscover her African-American religious heritage and spirituality and to enter her beloved Church “fully functioning.” She emphasized that cultural awareness had, as a prerequisite, intentional mutuality.

She was eager to learn from other cultures, but also wanted to share the abundance of her African-American culture and spirituality. Indeed, Sister Thea became a highly acclaimed evangelizer, teacher, writer and singer, sharing the joy of the Gospel and her rich cultural heritage throughout the nation.

Spurred by the need to return home to Canton to care for her aging parents, in 1978, Sister Thea, with the blessing, approval and permission of her superior and religious community, accepted an appointment by Bishop Joseph Bernard Brunini to direct the Office of Intercultural Affairs for the Diocese of Jackson. In this position Sister Thea continued to assail racial prejudice and promote cultural awareness and sensitivity. She was a founding faculty member of the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University in New Orleans. With the full support of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration, Sister Thea remained a member in good standing in her religious community.

In 1984, Sister Thea faced devastating challenges: both her parents died, and she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Her friends and students encouraged her to choose life. Sister Thea vowed to “live until I die” and continued her rigorous schedule of speaking engagements. Even when it became increasingly painful and difficult to travel as the cancer metastasized to her bones, she was undeterred from witnessing and sharing her boundless love for God and the joy of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

Donned in her customary African garb, Sister Thea would arrive in a wheelchair with no hair (due to the chemotherapy treatments) but always with her a joyful disposition and pleasant smile. She did not let her wheelchair, or the deterioration of her body keep her from one unprecedented event – an opportunity to address the U.S. bishops at their annual June meeting in 1989 at Seton Hall University in East Orange, N.J. Sister Thea spoke to the bishops as a sister having a “heart to heart” conversation with her brothers.

This well-crafted, yet at times quite spontaneous, message spoke of the Church as her “home,” as her “family of families” and as her trying to find her way “home.” She explained what it meant to be African-American and Catholic. She enlightened the bishops on African-American history and spirituality. Sister Thea urged the bishops to continue to evangelize the African-American community, to promote inclusivity and full participation of African-Americans within Church leadership, and to understand the necessity and value of Catholic schools in the African-American community. And when she was through she invited the bishops to move together, cross arms and sing with her the spiritual “We Shall Overcome.” She touched the hearts of the bishops, as evidenced by their thunderous applause and tears flowing from their eyes.

When asked by her dear friend and homilist for her funeral, Father John Ford, what to say at her funeral, Sister Thea responded: “Tell them what Sojourner Truth said about her eventual death, ‘I’m not going to die. I’m going home like a shooting star.’” And so she did, peacefully at 5 o’clock in the morning of March 30, 1990, in the home where she was reared in Canton. Sister Thea said that she wanted inscribed on her tombstone the simple, yet profound words: “She tried.” “I want people to remember that I tried to love the Lord and that I tried to love them…” She was buried beside her parents and an uncle at the Elmwood cemetery in Memphis, Tenn.

Sister Thea Bowman’s life was always one of Gospel joy, enduring faith and persevering prayer even in the midst of racial prejudice, cultural insensitivity and debilitating illness. Her personal holiness witnessed to the faith and endurance of her ancestors, the hope expressed in the spirituals, compassion for the poor and marginalized, her devotion to the Eucharist, and the radical love embodied by St. Francis of Assisi. Asked how she made sense of suffering, she answered, “I don’t make sense of suffering. I try to make sense of life…I try each day to see God’s will…”

Her life epitomized the words of Pope Francis in “Evangelii Gaudium”: “Indeed, those who enjoy life most are those who leave security on the shore and become excited by the mission of communicating life to others.” Sister Thea’s life is also a radiant example of Pope Francis’ “Gaudete et Exsultate,” in which the Holy Father wrote, “Your identification with Christ and His will involves a commitment to build with Him that kingdom of love, justice and universal peace.”

During her short lifetime of 52 years, many people considered her a religious sister undeniably close to God and who lovingly invited others to encounter the presence of God in their lives. She is acclaimed a “holy woman” in the hearts of those who knew and loved her and continue to seek her intercession for guidance and healing.

Today across the United States there are schools; an education foundation to assist needy students attend Catholic universities; housing units for the poor and elderly, and a health clinic for the marginalized that are named in her honor. Books, articles, catechetical resources, visual media productions, and a stage play have been written or created documenting her exemplary life, spirituality and ministry; prayer cards, works of art, statues, and stained-glass windows bear her image – all attesting to Sister Thea’s profound spiritual impact and example of holiness for the faithful.

— Source: www.sistertheabowman.com, the official website for her cause for canonization

Prayer for Thea Bowman

Ever loving God, who by Your infinite goodness inflamed the heart of Your servant and religious, Sister Thea Bowman, with an ardent love for You and the People of God; a love expressed through her indomitable spirit, deep and abiding faith, dedicated teaching, exuberant singing, and unwavering witnessing of the joy of the Gospel.

Ever loving God, who by Your infinite goodness inflamed the heart of Your servant and religious, Sister Thea Bowman, with an ardent love for You and the People of God; a love expressed through her indomitable spirit, deep and abiding faith, dedicated teaching, exuberant singing, and unwavering witnessing of the joy of the Gospel.

Her prophetic witness continues to inspire us to share the Good News with those whom we encounter; most especially the poor, oppressed and marginalized. May Sister Thea’s life and legacy compel us to walk together, to pray together, and to remain together as missionary disciples ushering in the new evangelization for the Church we love.

Gracious God, imbue us with the grace and perseverance that You gave Your servant, Sister Thea. For in turbulent times of racial injustice, she sought equity, peace and reconciliation. In times of intolerance and ignorance, she brought wisdom, awareness, unity and charity. In times of pain, sickness and suffering, she taught us how to live fully until called home to the land of promise. If it be Your Will, O God, glorify our beloved Sister Thea, by granting the favor I now request through her intercession (mention your request), so that all may know of her goodness and holiness and may imitate her love for You and Your Church. We ask this through Your Son and our Savior, Jesus Christ. Amen.

— Catholic Diocese of Jackson

Learn more

At www.sistertheabowman.com: Learn more about Sister Thea Bowman, watch a video from her 1989 talk to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, and find prayer and educational resources about her cause for canonization

At www.catholicnewsherald.com: Read more about the Church’s black Catholic saints, traditional black Catholic parishes in the Diocese of Charlotte, the roots of Black Catholic History Month and the diocesan African American Affairs Ministry