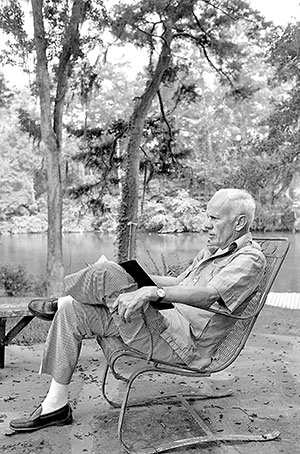

Walker Percy in his yard in Covington, La., in June 1977. (Jack Thornell | Associated Press) It is funny how one can look back at a most mundane moment and realize just how outrageously pivotal it actually was. For example, during my freshman year in college, I had a work-study job in my school’s library. With my affection for books, it seemed as though I had hit the jackpot with the best possible job. I didn’t anticipate the long stretches of boredom when we were overstaffed, combined with slow business at the circulation desk. But the librarian had a solution: reading the shelves. Idle workers were dispatched to various rooms of the library to read the shelves – that is, to look at the LC numbers and make sure the books were in order.

Walker Percy in his yard in Covington, La., in June 1977. (Jack Thornell | Associated Press) It is funny how one can look back at a most mundane moment and realize just how outrageously pivotal it actually was. For example, during my freshman year in college, I had a work-study job in my school’s library. With my affection for books, it seemed as though I had hit the jackpot with the best possible job. I didn’t anticipate the long stretches of boredom when we were overstaffed, combined with slow business at the circulation desk. But the librarian had a solution: reading the shelves. Idle workers were dispatched to various rooms of the library to read the shelves – that is, to look at the LC numbers and make sure the books were in order.

The best of all areas to be assigned was the basement, where the fiction stacks were housed. It was a playground of temptations. Read a few call numbers, straighten a few books, and succumb to the temptation to open those books that looked the least bit interesting. And if something looked particularly good, spend a few minutes perched on a stool next to the window – yes, there were windows, often open to a cool lake breeze – reading. For a freshman with the moral flexibility to read a book when she should have been reading spines, it was literary heaven.

It was during one of these moments, committing the sin of theft of wages, that I had one of the most significant and intensely educational experiences of my college career. I saw a book called “Love in the Ruins,” with the subtitle, “The Adventures of a Bad Catholic at a Time Near the End of the World.” It sounded promising. I had an intense fascination with Catholicism, and a book about a bad Catholic held promise.

“Now in these dread latter days of the old violent beloved U.S.A. and of the Christ-forgetting Christ-haunted death-dealing Western world I came to myself in a grove of young pines and the question came to me: has it happened at last?” Could anyone read this opening sentence and not be hooked? Here was a book that would not quickly be placed back on the shelf. This was one to legitimately take out and read. All the way through.

From that first reading as a callow 18-year-old Lutheran freshman of the most sophomoric pretensions, I nevertheless knew this wasn’t only a hilarious novel but something of depth. I was blessed with enough humility to remember this work and to return to it over the years, finding new depth and insight with every rereading. The book remained the same, but this reader grew and found an uncomfortable amount of present reality amid the absurdity. The world of protagonist Dr. Thomas More with his lapsometer is always funny but becoming ever more disquieting as life imitates prophetic art.

Walker Percy was born in Birmingham, Ala., in 1916 to a family of such tragedy that their despair and suicide-clouded history resembles a Southern Gothic novel. Percy’s father committed suicide when Walker was a young teen, and his mother died in a car accident shrouded in suspicion two years later. He and his two brothers were adopted by their bachelor uncle Will Percy, who raised them in the tradition of Southern manliness, scholarship and stoicism. Walker Percy’s first career was as a physician. But after being afflicted with tuberculosis while an intern in a New York hospital and taking a long, quiet recuperation that provided time for reading and thought, Percy chose to return to the South and pursue a deeper longing: the life of a writer. And it was as an adult that Percy (and his wife) converted to the Catholic Church, the faith of many of his Percy ancestors. This conversion of heart is of no small consequence; it is the spiritual essence that makes Percy’s writing more than great. The spiritual life of this man is what sets him apart from other authors who are only skilled wordsmiths and amusing storytellers.

Percy was a prolific writer, a teacher, an astute scholar in semiotics and a keen observer of life in general. It is possible to read Percy’s novels (and essays and articles and other books) with no consideration of the spirituality of the author. That is possible. But when his writings are approached in this manner – the approach I took as an ignorant freshman – so much is missed. The Christ-haunted, Christ-graced author who possessed such a superb way with words has something precious to tell us. We need only pay attention and be open to the movement of grace.

When you chat with Percy fans, there is the inevitable discussion of their favorite of his works. Some would say “The Moviegoer,” winner of the National Book Award in 1962. Others might offer “The Last Gentleman” or even the sublime, though disturbing, “Lancelot.” These are great books, deserving of thoughtful reading. But I will always say – and this is not just sentiment talking – “Love in the Ruins.” Start there. Start with “Love in the Ruins.”

Writing in 1980, the great literary scholar Dr. Ralph Wood goes so far as to say, “The novel seemed a piece of zany hyperbole when it was published in 1971. A decade later it reads like palpable prophecy.”

Ellyn von Huben is a native of Wisconsin, and has never lived more than five miles from the shores of Lake Michigan. She holds a degree in art history from Barat College in Lake Forest, Ill. This piece was originally published on Jan. 5, 2021, on WordonFire.org.

In the spring of 2008 I was a senior in college sitting in the backyard of a little white rental house near campus and I was weeping because an old man in a book had made the sign of the cross.

In the spring of 2008 I was a senior in college sitting in the backyard of a little white rental house near campus and I was weeping because an old man in a book had made the sign of the cross.

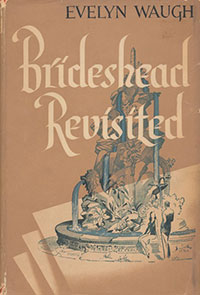

I was reading “Brideshead Revisited” for my 20th-century novel class. I had been delighted by its colorful characters and the author Evelyn Waugh’s brilliant humor, but slightly confused about where the story was going or why the book was hailed as a Catholic masterpiece.

The Catholic characters all seemed to be a mess, with failed marriages and scandalous decisions and addictions they knew were wrong. They were bad Catholics, people who could barely hold on to the cultural trappings of their faith. They were haunted by their sins, but they didn’t even attempt to hide them under a veneer of respectability. As a lifelong Protestant, I wondered: If Catholicism is true, wouldn’t Catholics behave better? What I wasn’t prepared for was the flood of grace waiting to overwhelm my heart in the final pages.

“Brideshead Revisited” is about the lost sheep of the historically Catholic and wealthy Flyte family and is narrated by their friend, agnostic Charles Ryder (fiance to the Flyte’s oldest daughter, Julia). When the family congregates because of the final illness of their patriarch, Lord Marchmain, the specter of death becomes a catalyst of grace.

Following years of self-imposed exile after abandoning his devout Catholic wife, now deceased, for a life of “freedom” with an Italian mistress, Lord Marchmain returns to the family estate in England to die. After firmly refusing the sacraments from the local parish priest and claiming that he has “not been a practicing member of your Church for twenty-five years,” the old man’s health further declines. The two Flyte children still practicing, Cordelia and Bridey, desperately desire him to die in a state of grace, hoping he will not refuse last rites before he expires. But to Charles’ great surprise, Julia Flyte, who left the Church years ago, is also determined that her father should not die estranged from God.

Can’t the old man who has scoffed at the faith be left to die in peace? Charles wonders. Why would Julia, whose life seems to deny every doctrine of the Church she has abandoned, become anxious for the soul of her dying father? Surely she doesn’t think it’s all true? If Lord Marchmain is losing consciousness, what’s the point of performing the sacrament at all? And if the crux of the matter is a soul’s contrition, why is it so important that a priest shows up? It all baffles Charles, and he interrogates the family regarding this sudden obsession with the sacraments and Lord Marchmain’s soul.

Charles is shocked to discover that the family members and Cara, Lord Marchmain’s mistress, have varying levels of devotion and understanding of Church teaching, yet all seem to agree that the sacraments matter. Cara, who has lived in sin for decades with Lord Marchmain and cannot be criticized for scrupulosity, closes the question by saying simply that when her death comes, “All I know is that I shall take very good care to have a priest.”

How is it possible that these bad Catholics would still, despite their wandering, be compelled to believe? Could the mark of baptism and the pull of sacramentals still draw them with the powerful residual effects of grace? With Cordelia and Bridey both absent, Julia makes the decision to call for the priest when it’s clear that Lord Marchmain is in his final hours. Charles watches the priest begins asking Lord Marchmain, who is too ill to speak, to give a sign that he is sorry for his sins and to receive God’s grace in the sacrament of the anointing of the sick.

Charles, despite his lack of faith, finds himself praying with Julia and Cara kneeling by the deathbed, “Oh God, if there is a God, forgive him his sins, if there is such a thing as sin.” His hostility to the faith is no match for the grace being poured out through a very ordinary priest in Lord Marchmain’s last rites. Once he is anointed Charles sees the old man bring a trembling hand to his forehead, and Charles worries that Lord Marchmain is about to obstinately wipe away the chrism oil in a final rejection of the Church. Instead, with his last ounce of strength, Lord Marchmain makes the sign of the cross.

This moment of grace will bring Julia back to her faith and bring Charles to it for the first time as he embraces prayers “ancient” and “newly learned.” But that powerful exhibition of grace didn’t just set their conversions in motion – it set mine in motion, too.

As I sat in my backyard weeping over a fictional character’s receptivity to God’s mercy, something clicked. Grace, sin, the sacraments, human failure and redemption – an indescribable awakening in my heart. I wanted that kind of powerful grace. I understood that the scandalous wandering of the Flytes was also my own wandering. Maybe my faults weren’t the cause of public scandal, but like the Flytes, I had chosen my sins over God, and like Charles, I was an outside observer being drawn against my will to the grace being offered me.

If the sacraments were real and powerful enough to change lives and restore lost souls, then the grace of God was waiting for me too. And I didn’t want to wait until my deathbed to receive it. Cordelia, the youngest Flyte daughter with the most charity and therefore the most clarity of vision, always has hope for her wandering siblings, knowing that “God won’t let them go for long, you know.” She compares the grace that will draw them home to an image from one of Chesterton’s Father

Brown stories about a thief who has been caught by “an unseen hook and an invisible line which is long enough to let him wander to the ends of the world and still to bring him back with a twitch upon the thread.”

I didn’t finish “Brideshead Revisited” and immediately sign up for RCIA. It wasn’t until a year later, when my son was born, that my husband and I were pushed across the Tiber by the desire for our firstborn to receive the sacrament of baptism. But Lord Marchmain’s holy death was a twitch upon the thread drawing my wandering heart, by God’s grace, closer to His mercy.

Haley Stewart is the managing editor of Word on Fire Spark and the author of “The Grace of Enough, Jane Austen’s Genius Guide to Life,” and “The Sister Seraphina Mysteries.” She lives in Florida with her husband and four children. This article originally appeared on www.wordonfire.org.