Sinner and sage

Considered one of Caravaggio’s best masterpieces, “The Entombment of Christ” was confiscated by the French for their newly opened Louvre Museum as Napoleon swept down the Italian peninsula in the late 18th century.

Considered one of Caravaggio’s best masterpieces, “The Entombment of Christ” was confiscated by the French for their newly opened Louvre Museum as Napoleon swept down the Italian peninsula in the late 18th century.

The painting was one of more than 100 works of art Pope Pius VI was forced to give up as part of a peace treaty between Revolutionary France and the Papal States in 1797.

However, when the masterpiece was returned in 1816, it did not end up back in its original home: a side chapel in the Oratorians’ Santa Maria in Vallicella Church, also known as “Chiesa Nuova,” in Rome. Pope Pius VII instead put it safely in his picture gallery, where it can be admired today as part of the Vatican Museums’ vast collection.

While the canvas, which measures 10 feet by 6.6 feet, survived the plunder, its deeper meaning and function as an altarpiece is usually lost on most visitors. As Quatremère de Quincy, a French architect who fiercely opposed taking art away from Italy, warned in 1796: “Eradicating the context in which a work was created irreparably impairs its legibility.”

To explain how to read Caravaggio’s piece “in situ,” the Oratorians invited Alessandro Zuccari, a leading expert on Caravaggio and professor of art history at Rome’s La Sapienza University, to give a lecture at their church on Jan. 24.

The massive oil painting was commissioned to decorate the wall above the altar in a chapel of the church. Completed in 1603, the work shows Nicodemus and the apostle John struggling with the heavy, lifeless body of Jesus to place him on an anointing stone and prepare his body for the entombment.

Caravaggio used Michelangelo’s Pietà in St. Peter’s Basilica for inspiration, Zuccari said, and created a similarly striking form of Jesus draped helplessly in someone’s arms and included a similar hand holding him up, gripping his flesh by the wound on his side.

It was also a nod to his namesake, he said. Born Michelangelo Merisi, Caravaggio wanted to be the Michelangelo Buonarroti “of the new century” and “emulate and outdo the great masters” with his new style.

In Caravaggio’s Entombment, three women are looking on with their own personal expression of grief and different gestures of prayer: the Blessed Virgin Mary extends her arms wide like a cross, Mary Magdalene bows her head and Mary, the wife of Clopas, throws her arms up and gazes toward the heavens.

Bathed in bright light, the crucified Jesus is the painting’s focal point, but his finger is firmly touching the anointing stone below with its sharp cornerstone edge glinting in the light and jutting out toward the viewer, Zuccari said. It is the prophetic sign of victory over death in Psalm 118:22, “The stone the builders rejected has become the cornerstone.”

However, when the painting can be seen at the altar during Mass, the genius of Caravaggio’s composition truly comes through, Zuccari said. A copy of Caravaggio’s Entombment was put above the altar in 1797. The copy “is not exactly the best,” he said, “but it is at least useful” for getting an idea.

Father Maurizio Botta, an Oratorian priest at the parish, demonstrated the effect for Catholic News Service Jan. 25.

The painting’s cornerstone falls precisely at the center of the altar where the priest stands.

When the priest elevates the host, it appears as if he is reaching up to receive the body on the wall and suddenly, for the congregants kneeling, Nicodemus’ eyeline is focused on the host, not the viewer – both critical cues for the faithful to understand the moment.

Father Botta explained he does the same demonstration during catechism classes to show the children “the relationship between Christ’s body and him alive in the Eucharist.”

Oratorian Father Simone Raponi, the organizer of the lecture with Zuccari, told Vatican Radio that Caravaggio really understood “the modern sense of spirituality” promoted by the Oratorian’s founder St. Philip Neri.

So much attention has been given to Caravaggio’s “difficult” personality and behavior, that his reputation as “the cursed artist” or as an anti-conformist further risks “removing Caravaggio from the real authentic (artistic, spiritual and cultural) context in which his work emerges and matures,” he said Jan. 20.

“In my opinion, he understood the meaning of modern spirituality: the divine can be glimpsed in reality” and not sought out in the abstract and what is beyond this world, he said.

Caravaggio was very close to and collaborated with members of the Oratorians while in Rome, he said, and understood the order’s charism.

It is not known whether Caravaggio ever met St. Philip, who died in 1595, Father Raponi said, but there is a legendary exchange between the two, which, whether it actually occurred or not, offers a life lesson.

He said, “St. Philip tells Caravaggio: ‘I see two wolves inside of you, one fighting the other, trying to tear each other apart.’ And the painter asks: ‘Which one will win?’ St. Philip responds, ‘The one you feed more.’”

St. Philip saw faith as something that had to come from within as an intimate relationship with God and to grow by “nourishing the soul,” he said.

“So, these lights and shadows that you somehow find in Caravaggio’s paintings, these two wolves, perhaps, that struggle, St. Philip teaches that the nourishment should be given to the light in Caravaggio’s life and in our lives,” he said.

— Carol Glatz

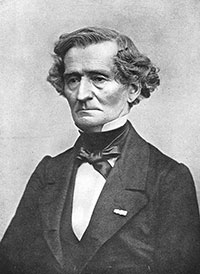

One of the most important aspects of the Christmas season is the music we hear, and over the centuries, many composers have contributed significantly to the genre. One of the more unique works is the sacred trilogy “L’enfance du Christ” (“The Childhood of Christ”) by French composer Hector Berlioz.

One of the most important aspects of the Christmas season is the music we hear, and over the centuries, many composers have contributed significantly to the genre. One of the more unique works is the sacred trilogy “L’enfance du Christ” (“The Childhood of Christ”) by French composer Hector Berlioz.

To make ends meet, Berlioz frequently resorted to writing music criticism in the typical French style: full of wit, humor and just enough sarcasm to be endearing. The same writing style is found in his memoirs. In the first chapter, in a translation by David Cairns, the composer touches upon his childhood in the faith:

“Needless to say, I was brought up in the Catholic and Apostolic Church of Rome. This charming religion (so attractive since it gave up burning people) was for seven whole years the joy of my life, and although we have long since fallen out I have always kept the most tender memories of it.”

Although lesser known among this composer’s body of work, “The Childhood of Christ” is a fine choice to commemorate the entire Christmas season. Although never referred to as an oratorio by the composer, it is considered as such by contemporary listeners. (Readers may be familiar with oratorios such as the famous “Messiah” by G.F. Handel, the first part of which is also appropriate for the Christmas season).

Berlioz started composing the work in 1850 and finished it four years later. It is scored for vocal soloists, choir and orchestra and is separated into three parts: “Herod’s Dream,” “The Flight Into Egypt” and “The Arrival at Sais.” The events in Part One do not follow Scripture chronologically. For example, Scene IV depicts Herod decreeing the deaths of the innocents prior to the scene entitled “The Manger at Bethlehem.” The latter is a duet between our Blessed Mother and St. Joseph, and since the Gospels recorded no words at the birth, a bit of creative license was used that proved remarkably effective.

Berlioz, a master orchestrator, begins “The Manger at Bethlehem” with woodwinds, including the English horn (an alto oboe) that provides an outdoor/shepherd ambience. Specific keys have long been associated with moods or emotions, and in the early 19th century, the key of A-flat major was associated with death and the grave. A composer often purposely chooses a key because of these historical associations and at first glance, one might find A-flat major to be an odd tonality for depicting the Nativity. However, as Venerable Fulton Sheen explained in his “Life of Christ,” Jesus was the only person born to die, which makes the choice of key for Christ’s birth profoundly appropriate. (A similar connection is frequently made with the Magi’s gift of myrrh.)

In the Kalmus edition of “Berlioz’s Complete Works,” the translation of Mary’s lullaby reads: “Sweet, holy babe, these sweet herbs so tender give the sheep thou lovest … see they come to Thee bleating! They are so meek. Let them graze on the meadow, lest they shall suffer hunger.”

One can clearly see the powerful references to Christ’s future role as the Good Shepherd in the choice of text here. She is subsequently joined by St. Joseph before the scene ends with an unassuming, instrumental conclusion.

Berlioz is frequently heralded for his great dramatic prowess, but this section of the “L’enfance du Christ” demonstrates his sensitivity and is a perfect representation of the peaceful Nativity of Our Lord.

— Christina L. Reitz

Listen online

Listen to a rendition of Hector Berlioz’s “L’enfance du Christ”